For the past six months, Burton Cummings, founding singer and songwriter of classic rock group The Guess Who, has been in a bitter legal dispute to wrest control of his old band’s legacy, reports Rolling Stone. Now he’s adopting an aggressive and relatively unheard of approach to make that happen: giving up on certain royalties so the band can’t play his songs.

As Rolling Stone previously reported, Cummings and original Guess Who guitarist Randy Bachman sued the current iteration of The Guess Who (as well as the band’s original drummer and bass player Garry Peterson and Jim Kale) last October, alleging that the group that currently holds The Guess Who trademark is “a cover band” using the original group’s recording in ads “in an effort to boost the Cover Band’s ticket sales for live performances and to give the false impression that Plaintiffs are performing.”

That case is still ongoing, and a federal judge denied the band’s motion to dismiss the founders’ suit earlier this week. But as the suit continues, Cummings has taken a nuclear action, terminating the performing rights agreements for all The Guess Who songs he wrote, removing the copyright protections that allow the band (or anyone else) to perform hits like “American Woman,” “These Eyes,” and “No Time” at a concert. In effect, he shot himself in the foot to try to shoot the band in the face.

“I’m willing to do anything to stop the fake band; they’re taking [Bachman and my] life story and pretending it’s theirs,” Cummings tells Rolling Stone. “They’re not the people who made these records, and they shouldn’t act like they did. This doesn’t stop this cover band from playing their shows, it just stops them from playing the songs I wrote. If the songs are performed by the fake Guess Who, they will be sued for every occurrence.”

Cummings’ strategy is both very aggressive and particularly rare. Two music attorneys with no affiliation to the case tell Rolling Stone they’d never seen such a strategy before. Cummings’ attorney Helen Yu spent several months working to get the license properly terminated. She adds that part of why it’s so unheard of for artists to consider such a strategy is that often, writers don’t own the publishing, which is required to pull both ends of the license.

“Not a lot of artists are both the writer and the publisher on their songs, and Burton Cummings fortunately is, so this is a very rare case where the artist can take this action,” Yu says. “And I think this situation shows the direct nexus between their false advertising and who they say they are.”

Read the full report at Rolling Stone

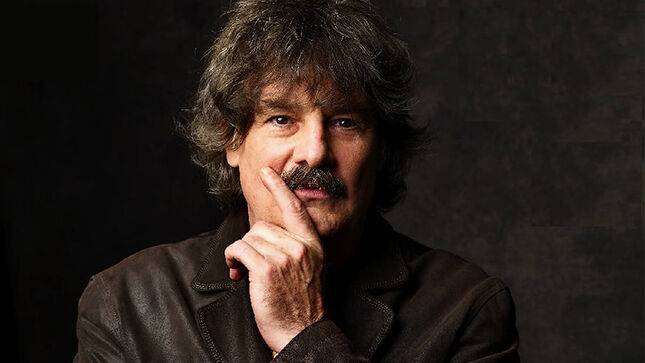

(Burton Cummings photo - Shillelagh Music)